On September 8th, 1904, Ivan Pavlov received the Nobel Prize in Physiology for his groundbreaking work on the digestive system that led to our understanding of “Conditioned Reflexes.” The essence of his research illuminated our understanding of how repeated stimuli can lead to specific behavioral responses in animals.

What does Pavlov’s work have to do with our relationship with time and the malleable pathways of our brain? Quite a bit, as it turns out.

The Structure of Time

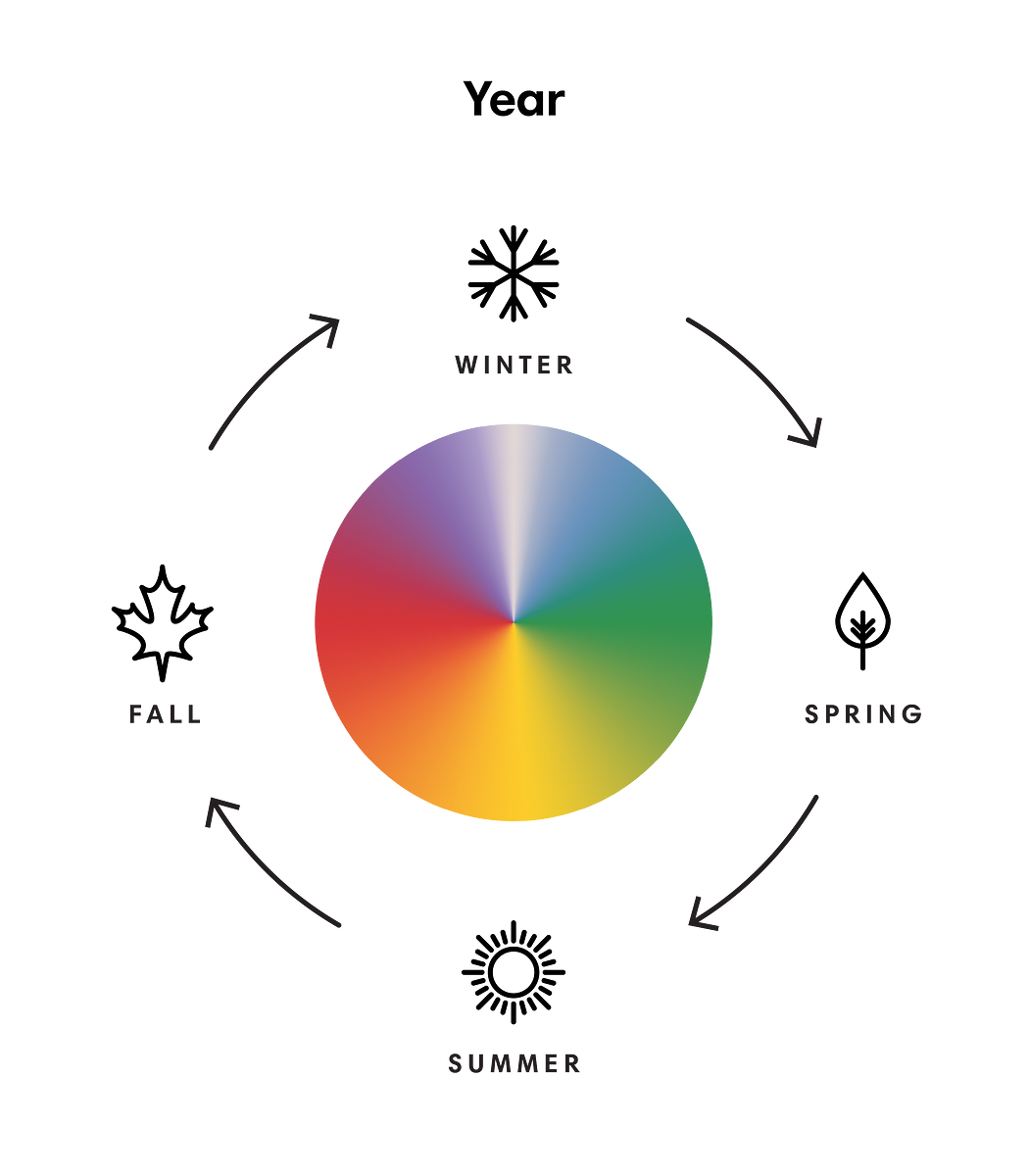

Firstly, it’s essential to recognize how we’ve conditioned ourselves to perceive time. Much like Pavlov’s dogs came to associate the ringing bell with food, we’ve trained ourselves to view time in a narrow framework of seconds, minutes, and hours. This notion of time is not innate but conditioned through repeated exposure to clocks, schedules, and, of course, the incessant ‘tick-tock’ that permeates our daily lives.

The Art of Habit

The magic in Pavlov’s discovery isn’t just about how conditioning works; it’s in the revelation that habits, once formed, can be changed. Think of how amazed Pavlov may have been to learn about the emerging science of neuroplasticity. Previously, the structure of the human brain was thought to be fixed past a certain age. However, recent research has shown that our neural pathways are far more flexible than once thought. What does this mean for us? Simply put, the way we’ve trained ourselves to perceive and use time is open for interpretation; it can be contracted or even expanded.

The Power of The Present

Change is most potent in the present moment. Forming a new habit is about acknowledging the existing pattern and consciously deciding to shift it through repetition. If James Clear’s outrageously successful book Atomic Habits is any indication, the excitement surrounding our ability to shift our thinking, alter our behavior and transform our lives is making our mouths water. Let’s apply this principle of transformation to our perception of time. The rigidity with which we view time might be appropriate for catching a train but not necessarily for more nuanced, emotionally impactful moments.

Being fully present in an interaction with a loved one doesn’t fit neatly into a schedule or a conventional clock’s measurement. Very few of us can recall the exact second of our first kiss, but the moment is no less significant because of it. We can break free from our limited time expectations without losing our ability to catch a plane. Much like you can train yourself to wake up without an alarm, you can prepare yourself to be present in a conversation, to listen without planning your following sentence, and to smile without expecting a specific response.

Sculpting Time

If repetition has conditioned our relationship with time, then it has the potential to recondition it as well. With the liberating science of neuroplasticity, we’re not prisoners to our past conditioning; we’re artists capable of sculpting new forms from old material.

We have the agency to alter our conditioned behavior of looking up at a conventional clock and orienting ourselves to the quantitative scarcity of the moment. It is now possible to shift the context of time by orienting ourselves with a device like The Present timepiece.

This kinetic sculpture utilizes motion to render a qualitative and abundant perception of the moment to help form new expectations around the story we tell ourselves about time.

What’s crucial to understand is that the power to reshape our perception of time is within our grasp. Pavlov’s Nobel Prize wasn’t just a recognition of the conditioned reflex; it was a precursor to the transformative power of habit. The act of being conditioned holds the power and potential to recondition. So, the next time you find yourself primed to urgency and anxiety by conventional time, remember you have the chisel in your hand. You can sculpt a different relationship with time, one that serves not just your schedule but also your spirit.

Leave a comment: